Archive

- Home

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- January 2006

- June 2005

- May 2005

- April 2005

- February 2005

- December 2004

- November 2004

- October 2004

- August 2004

- July 2004

- June 2004

- May 2004

- February 2004

- January 2004

- December 2003

- August 2003

- July 2003

- June 2003

- May 2003

- March 2003

- January 2003

- December 2002

- October 2002

- May 2002

- April 2002

- February 2002

- January 2002

- August 2001

- May 2001

- April 2001

- February 2001

- August 2000

- July 2000

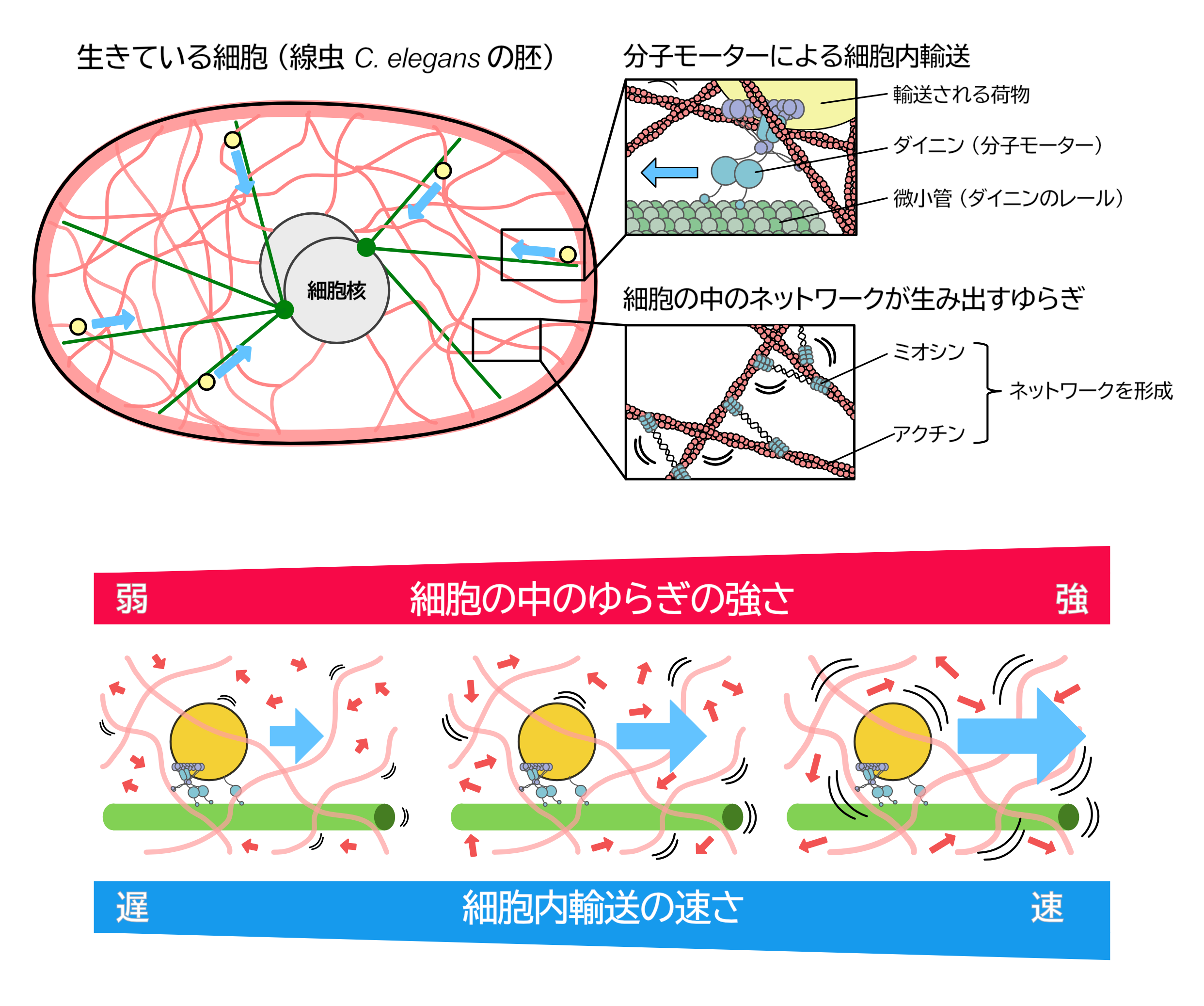

Fluctuation in the cytoplasm enhances directed transport

Kimura Group • Cell Architecture Laboratory

Active fluctuations of cytoplasmic actomyosin networks facilitate dynein-driven transport

Takayuki Torisawa, Kei Saito, Ken’ya Furuta, Akatsuki Kimura

iScience (2025) Volume 28, Issue 12 114096 DOI:10.1016/j.isci.2025.114096

Inside cells, molecular motors transport cargo through a highly crowded cytoplasmic environment. While such an environment is assumed to hinder transport, its precise effect remains unclear. Here, we investigated how the dynamics of cytoplasmic environments affect dynein-driven transport in C. elegans early embryos. In living embryos, we found that an artificial dynein-cargo complex exhibited significantly faster transport than in vitro, indicating an active acceleration mechanism in vivo. By altering the activity of actomyosin networks, we found that dynein-driven transport was accelerated by actomyosin-driven cytoplasmic fluctuations, with speed increasing upon myosin upregulation and decreasing upon its depletion. Furthermore, in vitro force measurements of dynein suggest that the asymmetric force response to random forces, generated by fluctuating dynamics of actomyosin networks, may contribute to acceleration. This study provides insights into a regulatory mechanism of molecular motors within fluctuating cytoplasm, harnessing cytoplasmic fluctuations to enhance transport efficiency in a highly crowded environment.

Figure: Model summarizing the biphasic change in local chromatin dynamics during doxycycline-induced transformation of EMR cells. The blue curve denotes a transient rise in local chromatin mobility after induction (orange arrow) followed by a return to baseline (green arrow). The increase coincides with elevated active histone marks (H3/ H4 acetylation) and transcription; dynamics subsequently restabilize while oncogene expression and tumor growth persist. Metabolic reprogramming may contribute to this process.

SOKENDAI Student Kim Jaeha Receives Best Poster Award

Kim Jaeha, a D4 student of the Genome Diversity Laboratory (Mori Laboratory) at the National Institute of Genetics, received the Best Poster Award at the international symposium 2nd Asian Genetics Consortium Conference (AGCC 2025), held from Friday, November 14 to Sunday, November 16, 2025, at the Numazu City Library.

▶ Award-Winning Poster title:

Behavioral phase transitions in the migratory locust, Locusta migratoria, are related to changes in gut microbiome composition

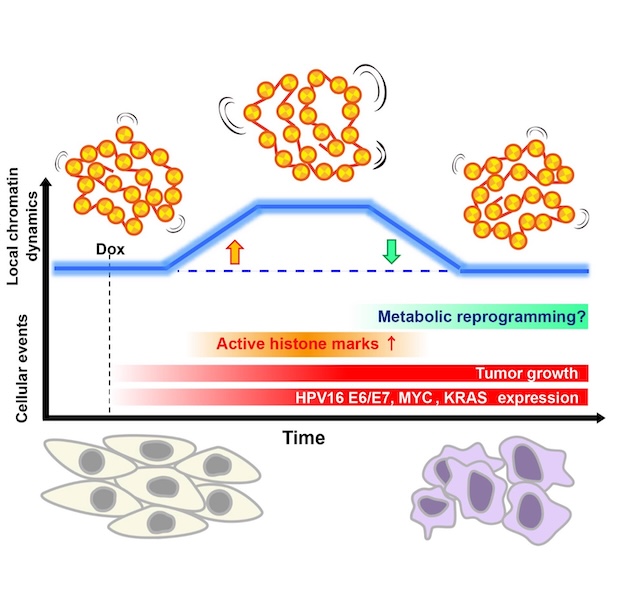

Chromatin dynamics in human transformed cells

Maeshima Group / Genome Dynamics Laboratory

Single-nucleosome imaging uncovers biphasic chromatin dynamics in inducible human transformed cells

Aoi Otsuka, Masa A. Shimazoe, Shigeaki Watanabe, Katsuhiko Minami, Sachiko Tamura, Tohru Kiyono, Fumitaka Takeshita, and Kazuhiro Maeshima* (*Corresponding author)

Cell Structure and Function (2025) Advance online publication DOI:10.1247/csf.25147

In eukaryotic cells, genomic DNA folds into nucleosomes to form dynamic domains encompassing euchromatin and heterochromatin. Although many cancer-associated changes in chromatin state and higher-order structure have been reported, how chromatin behavior evolves over time during carcinogenesis has remained unclear.

SOKENDAI students Aoi Otsuka (SOKENDAI Special Researcher) and Masa A. Shimazoe (JSPS DC1), postdoctoral researcher Katsuhiko Minami, technical staff member Sachiko Tamura, and Professor Kazuhiro Maeshima of the Genome Dynamics Laboratory, in collaboration with Visiting Researcher Dr. Tohru Kiyono (also a Visiting Researcher at the Sasaki Institute (Sasaki Foundation)), Project Researcher Dr. Shigeaki Watanabe, and Division Chief Dr. Fumitaka Takeshita at the National Cancer Center, established “EMR” human epithelial cells that inducibly express the oncogenes HPV16 E6/E7, MYC, and KRAS upon doxycycline treatment. Upon induction, EMR cells exhibited cancer-like traits—accelerated proliferation, loss of contact inhibition, soft-agar growth, and tumor formation in nude mice. Live-cell single-nucleosome imaging revealed a biphasic pattern in chromatin dynamics: no change at days 1–3, a transient increase at days 5–7, and a return to baseline by week 4. During this window of increased mobility, histone H3/H4 acetylation and transcription were elevated. Together, these results suggest that oncogene induction causes a transient chromatin “loosening” accompanied by widespread acetylation and transcriptional activation, followed by restabilization of chromatin dynamics even while oncogene expression and tumor growth persist.

This work demonstrates at the single-nucleosome level that the physical behavior of chromatin is reorganized over time during transformation, and that chromatin dynamics can serve as a physical readout of the cancer stage and cellular adaptation.

Funding: JSPS and MEXT KAKENHI (JP23K17398, JP24H00061, JP23KJ0998, JP24KJ1161), JST SPRING JPMJSP2104, and the Takeda Science Foundation.

Figure: Model summarizing the biphasic change in local chromatin dynamics during doxycycline-induced transformation of EMR cells. The blue curve denotes a transient rise in local chromatin mobility after induction (orange arrow) followed by a return to baseline (green arrow). The increase coincides with elevated active histone marks (H3/ H4 acetylation) and transcription; dynamics subsequently restabilize while oncogene expression and tumor growth persist. Metabolic reprogramming may contribute to this process.

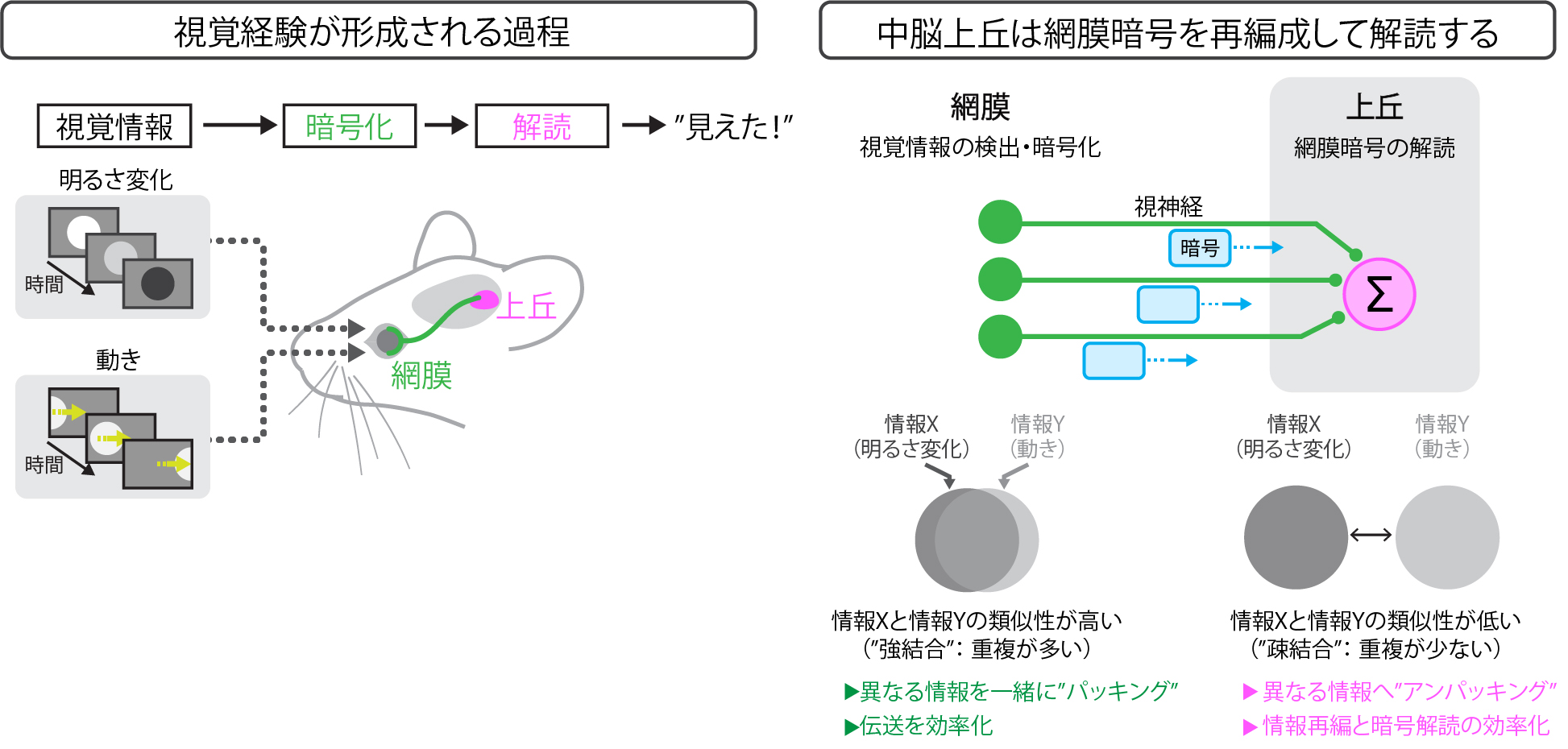

Decoupling of visual feature selectivity in the retinocollicular pathway

Press release

Decoupling of visual feature selectivity in the retinocollicular pathway

Ole S. Schwartz, Akihiro Matsumoto, Haruka Yamamoto, and Keisuke Yonehara

Current Biology 2025 DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2025.11.050

![]() Press release (In Japanese only)

Press release (In Japanese only)

The retina is composed of discrete functional cell types that are also characterized by distinct morphology and gene expression. It remains, however, unclear whether similar discrete functional cell types exist in the visual regions downstream of the retina. Here we used two-photon calcium imaging to investigate the response space structure in the retina and in the superficial layers of the mouse superior colliculus (SC), a major retinorecipient area. We found that while retinal ganglion cells showed a clear dependence between responses to luminance and motion, responses to the two stimuli exhibited weaker couplings in collicular neurons. Because of this decoupling, functional clustering based on responses to both luminance and motion had significantly reduced separability compared to clustering based on responses to either. Our work suggests that the SC is not simply a relay station for retinal inputs, but rather generates novel feature selectivity that diversifies cellular responses, perhaps through nonlinear neural processes involving the decoupling and recoupling of retinal ganglion cell’s feature selectivity.

(Left) The visual information processing pathway. Visual information is detected and encoded in the retina and then transmitted to the superior colliculus.

(Right) In the retina, the mutual information between neural activities representing two types of visual information—brightness change (information X) and image motion (information Y)—is high. In the superior colliculus, the redundancy present in the retinal code is decoupled.

Revealing the shared features of “Hard-to-synthesize” proteins in Bacteria — and discovering unique protein groups that actively exploits them

Press release

Evolutionary Adaptation of Bacterial proteomes to Translation-Impeding Sequences

Keigo Fujiwara, Naoko Tsuji, Karen Sakiyama, Hironori Niki, and Shinobu Chiba

The EMBO Journal (2025)

![]() Press release (In Japanese only)

Press release (In Japanese only)

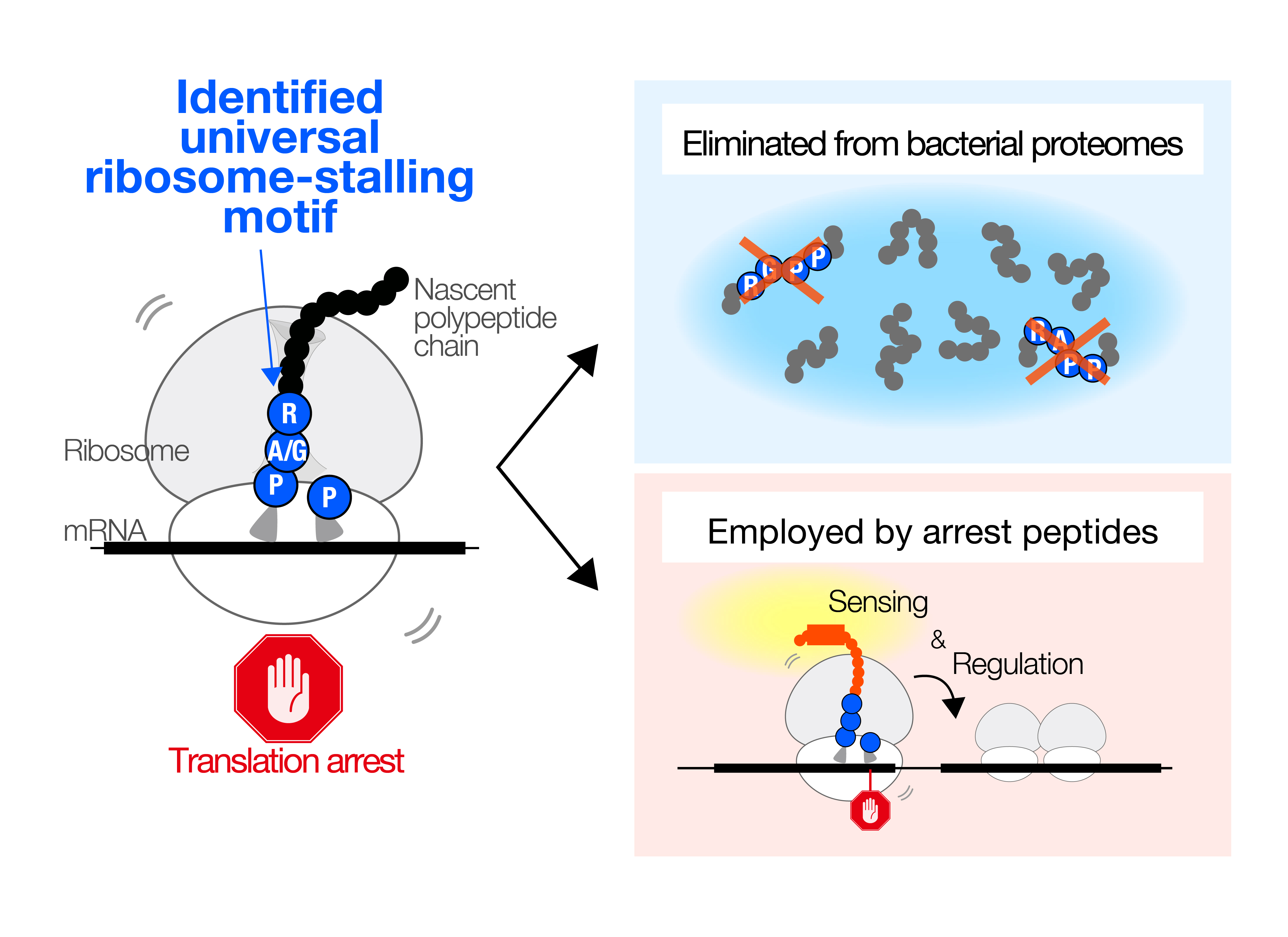

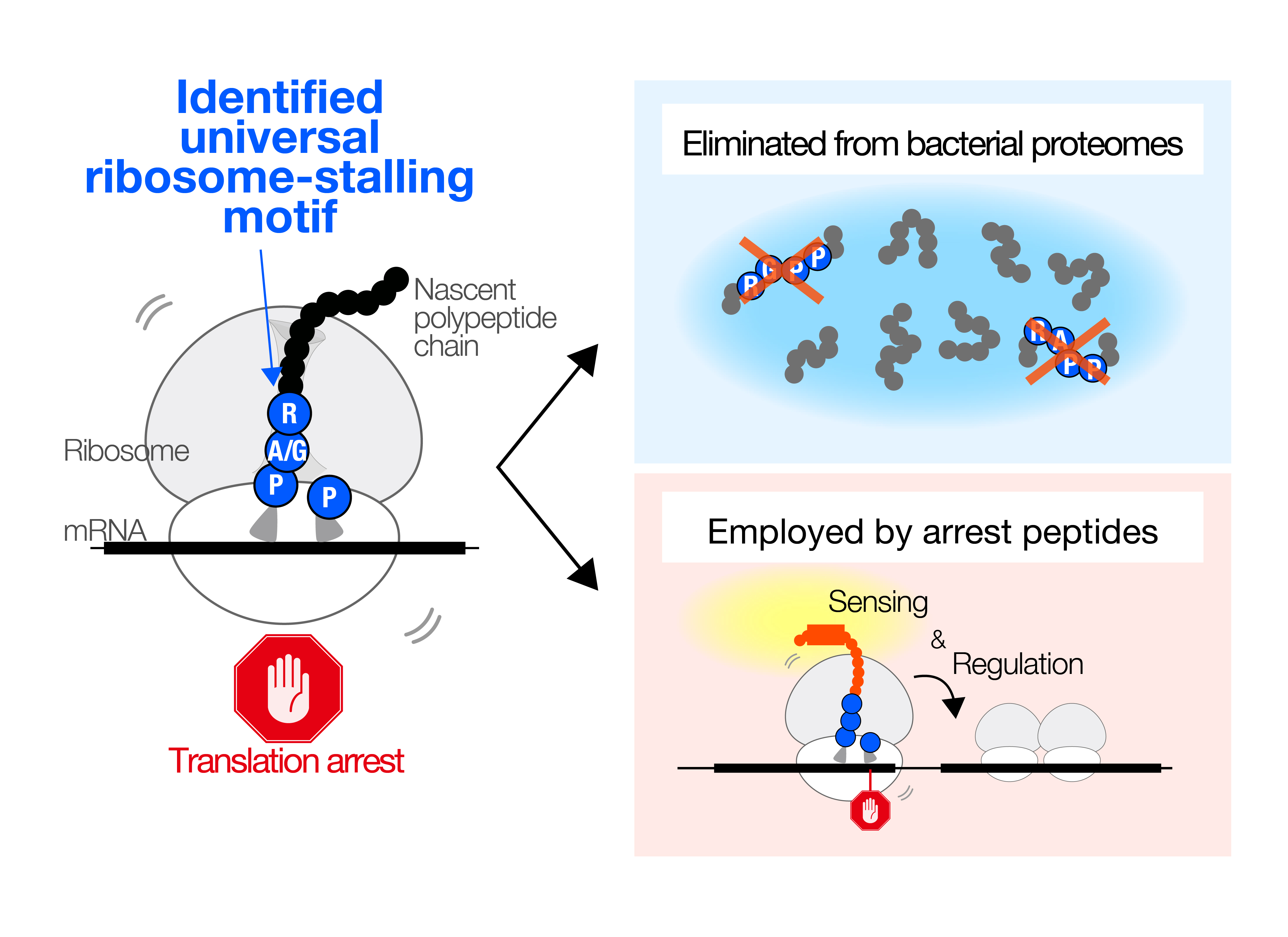

In this study, we revealed that diverse bacteria on Earth share amino acid sequences that are difficult for them to synthesize. Because amino acids are essential building blocks of proteins, cells cannot efficiently produce proteins that contain such translation-challenging sequences. Indeed, a comprehensive analysis conducted across the bacterial domain showed that these translation-challenging sequences are rarely found within bacterial proteins, suggesting that bacteria have evolutionarily avoided using them.

In contrast, we also discovered that these sequences frequently appear near the ends (carboxyl termini) of relatively small proteins. Bioinformatic analyses further indicated that such proteins likely play important and diverse roles in helping cells adapt to fluctuating environmental conditions.

Together, this work demonstrates that translation-challenging sequences, although generally disadvantageous and evolutionarily excluded from most proteins, can be repurposed by bacteria as functional elements. By leveraging the “difficulty” of translating these sequences, various bacteria appear to have evolved unique strategies to better cope with environmental changes.

Figure:We identified patterns of “translation arrest-causing amino acid sequences” that occur across many bacteria (left). Although such sequence patterns are generally eliminated during evolution (upper right), some bacteria have instead evolved unique mechanisms that leverage this inherent synthesis difficulty to support important cellular functions (lower right)

Revealing the shared features of “Hard-to-synthesize” proteins in Bacteria — and discovering unique protein groups that actively exploits them

Press release

Niki Group / Microbial Physiology Laboratory

Evolutionary Adaptation of Bacterial proteomes to Translation-Impeding Sequences

Keigo Fujiwara, Naoko Tsuji, Karen Sakiyama, Hironori Niki, and Shinobu Chiba

The EMBO Journal (2025)

In this study, we revealed that diverse bacteria on Earth share amino acid sequences that are difficult for them to synthesize. Because amino acids are essential building blocks of proteins, cells cannot efficiently produce proteins that contain such translation-challenging sequences. Indeed, a comprehensive analysis conducted across the bacterial domain showed that these translation-challenging sequences are rarely found within bacterial proteins, suggesting that bacteria have evolutionarily avoided using them.

In contrast, we also discovered that these sequences frequently appear near the ends (carboxyl termini) of relatively small proteins. Bioinformatic analyses further indicated that such proteins likely play important and diverse roles in helping cells adapt to fluctuating environmental conditions.

Together, this work demonstrates that translation-challenging sequences, although generally disadvantageous and evolutionarily excluded from most proteins, can be repurposed by bacteria as functional elements. By leveraging the “difficulty” of translating these sequences, various bacteria appear to have evolved unique strategies to better cope with environmental changes.

Figure:We identified patterns of “translation arrest-causing amino acid sequences” that occur across many bacteria (left). Although such sequence patterns are generally eliminated during evolution (upper right), some bacteria have instead evolved unique mechanisms that leverage this inherent synthesis difficulty to support important cellular functions (lower right)

Genomes of Two Wild Japanese Cherries Unveiled

Koide Group / Mouse Genomics Resource Laboratory

Chromosome-scale genomes of two wild flowering cherries (Cerasus itosakura and C. jamasakura) provide insights into structural evolution in Cerasus

Kazumichi Fujiwara, Atsushi Toyoda, Toshio Katsuki, Yutaka Sato, Bhim B Biswa, Takushi Kishida, Momi Tsuruta, Yasukazu Nakamura, Takako Mochizuki, Noriko Kimura, Shoko Kawamoto, Tazro Ohta, Ken-Ichi Nonomura, Hironori Niki, Hiroyuki Yano, Kinji Umehara, Chikahiko Suzuki, Tsuyoshi Koide

DNA Research (2025) DOI:10.1093/dnares/dsaf031

Japan’s iconic cherry trees hold deep cultural significance, yet chromosome-scale genomic resources for their wild relatives have been lacking. The Sakura 100 Genome Consortium, led by the National Institute of Genetics and the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, has now produced the first high-quality, chromosome-scale genomes of Cerasus itosakura (Edohigan) and C. jamasakura (Yamazakura).

The genomes show exceptional completeness and reveal both broad conservation and key species differences. Notably, a 1.84-Mb inversion on chromosome 8 was identified in C. itosakura, providing new insight into lineage-specific chromosomal evolution. Differences in rRNA gene cluster organization further highlight genomic diversity within Cerasus.

Using these new references, the team reconstructed the haplotypes of the ornamental cultivar ‘Somei-yoshino’, confirming its hybrid origin from C. itosakura and C. speciosa.

This work advances the understanding of cherry evolution and offers a crucial foundation for breeding, taxonomy, and conservation.

A–B : Flowers and trees of C. itosakura. C-D:Flowers and trees of C. jamasakura. E: Chromosome-level genome structures of C. jamasakura and C. itosakura. F: A large inversion identified on chromosome 8 of C. itosakura. This inversion is not observed in C. speciosa, C. jamasakura, or C. campanulata.

This work was supported by grants from ROIS (Research Organization of Information and Systems).

Uncovering the principle by which DNA replication initiation sites are determined in the human genome

Press release

Regulated TRESLIN-MTBP loading governs initiation zones and replication timing in human DNA replication

Xiaoxuan Zhu, Atabek Bektash, Yuki Hatoyama, Sachiko Muramatsu, Shin-Ya Isobe, Chikashi Obuse, Atsushi Toyoda, Yasukazu Daigaku, Chun-Long Chen and Masato T. Kanemaki

Nature Communications 2025 DOI:10.1038/s41467-025-66278-7

![]() Press release (In Japanese only)

Press release (In Japanese only)

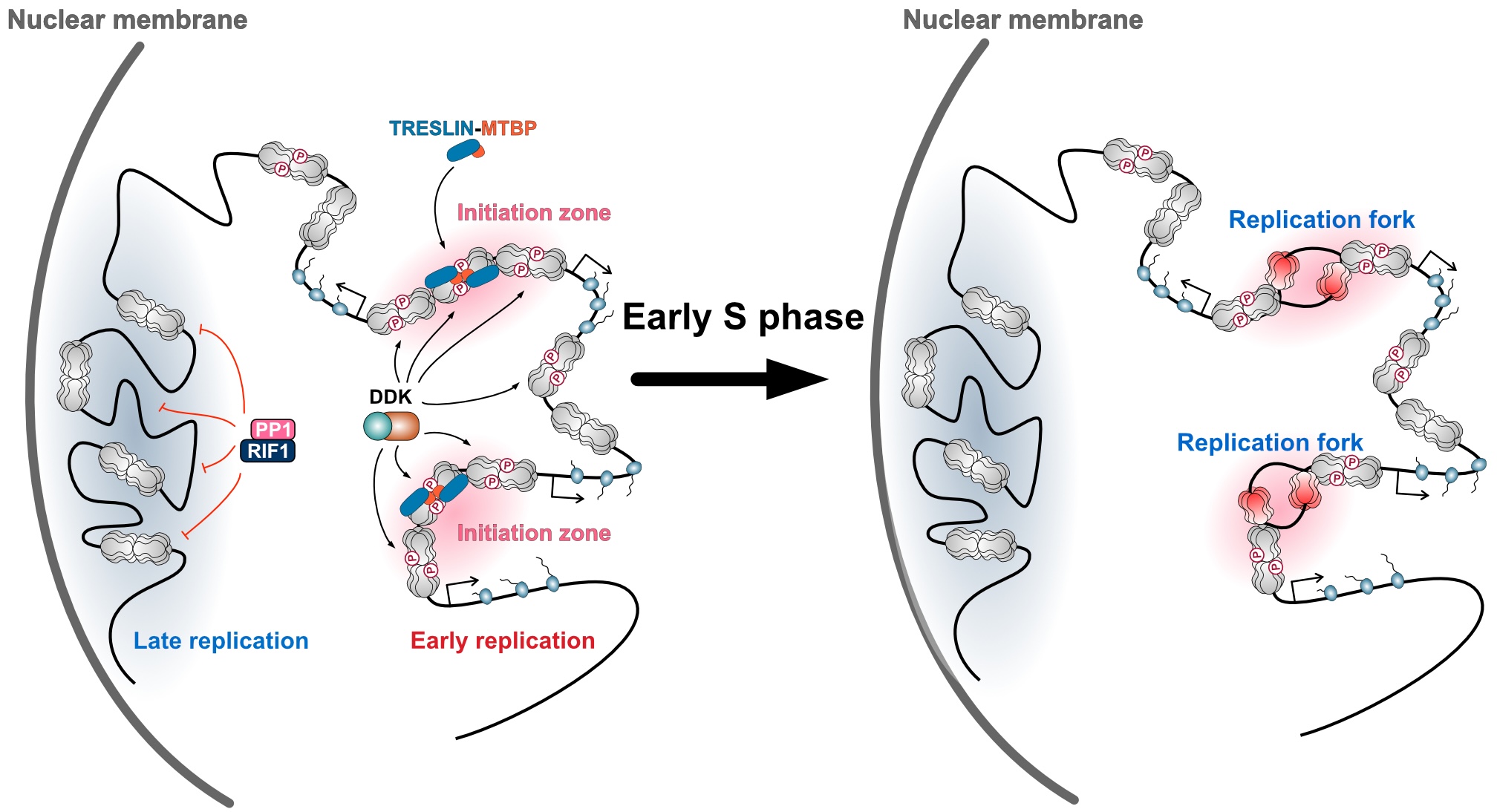

When cells proliferate, genomic DNA is precisely duplicated once per cell cycle. Abnormalities in this DNA replication process can cause alterations in genomic DNA, contributing to cellular ageing, cancer, and hereditary diseases. Therefore, understanding how cells replicate their DNA is crucial for elucidating fundamental biological processes, diseases, and even evolution.

Traditionally, DNA replication has been studied in microorganisms such as E. coli and yeast. In these organisms, the locations where DNA replication begins (replication origins) are determined by specific DNA sequences. However, in most eukaryotic cells, including human cells, the DNA sequence itself does not dictate where replication starts. For decades, it remained a mystery how and where replication is initiated within the human genome.

To address this, Professor Masato Kanemaki and his team including the first author, Dr Xiaoxuan Zhu, at National Institute of Genetics developed a new high-precision method, LD-OK-seq (Ligase Depletion-Okazaki sequencing), to detect replication initiation regions in the human genome. By further analysing the proteins bound to these regions, they uncovered the fundamental principle by which human cells determine replication initiation sites.

Their findings revealed that, except for actively transcribed gene regions, human cells possess the ability to initiate DNA replication from almost anywhere in the genome. This capability arises from the widespread binding of an enzyme called the MCM helicase, which is essential for DNA replication. Moreover, they discovered that during the early S phase, replication frequently begins in intergenic regions (areas between transcribed genes), and that these sites are determined by the binding of TRESLIN-MTBP, a protein complex that activates the MCM helicase. They also identified an antagonistic regulatory system that modulates the binding of TRESLIN-MTBP to MCM.

These discoveries answer the fundamental question of how human cells initiate genome replication, providing new insights into diseases caused by replication abnormalities—such as genomic instability disorders, cancer, aging, and hereditary diseases—as well as into genome evolution. In the long term, this work may also lay the foundation for technologies that enable artificial control of DNA replication.

This study was conducted through an international collaboration between the research group of Professor Masato Kanemaki and Project Professor Atsushi Toyoda at the National Institute of Genetics, Professor Chikashi Obuse at The University of Osaka, Dr. Yasukazu Daigaku at the Cancer Institute of JFCR, and Professor Chun-Long Chen at Curie Institute in France. The research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants (JP23H02463, JP21H04719, JP23H04925, JP25H00979), Platform for Advanced Genome Science (JP22H04925), JST FOREST (JPMJFR204X), JST CREST (JPMJCR21E6), and AMED ASPIRE (JP25jf0126015).

Figure: The MCM helicase is broadly bound across genomic DNA in regions outside actively transcribed genes, and its phosphorylation is antagonistically regulated by the kinase DDK and the phosphatase RIF1–PP1. The sites of replication initiation are determined when the TRESLIN–MTBP complex is recruited to the phosphorylated MCM helicase.